My uncle Jed has always referred to Melville’s Moby Dick as a cathedral. The allusion filled my mind with images of leaky high vaulted ceilings and sopping wet church pews strewn with seaweed. Like the sea, I imagined the novel to be an ocean. I figured it to be near impenetrable and too vast for me to fathom. Since my early twenties I’ve often considered taking up the challenge, but always hesitated, telling myself that I’m still too young to read Melville’s masterpiece.

More times than not we read a particular novel because it’s recommended or given to us. Often our next read is laying on a table or a counter top when we’re between books and we figure that it’s worth a look. However, there are also times when a book finds you. The times when a novel so happens to fall on your lap and for no good reason you open it and it somehow seems to be tailored to your current life — it’s a remarkable occurrence that defies mere coincidence. It‘s as if you needed it and the novel gods tucked a special something under your pillow for you to find in the morning.

I found Moby Dick, or rather Moby Dick found me, after I had recommended it to a friend. I had no idea why I had recommended a book I’ve never read to a friend, but he seemed desperate to engage in some kind of material that mirrored his own feelings of being lost at sea. The more I thought about it, I realized that I was recommending Moby Dick to myself.

It was over two weeks ago that I was rummaging through my brother’s nightstand for a lighter when I found a 1961 paperback edition of the novel partially exposed under the corner of his bed. I would like to say that it was glowing, but in reality it looked incredibly worn out and ready to burst at the seams. As I’ve been coasting through it, pages have come loose from the spine and drifted to the floor; this particular copy will most likely never be read by another.

For four of the past five years I’ve been living outside of the United States. My hometown of Seattle—the beautiful emerald city in which I grew up in—by my mid-twenties began to feel like a prison. I felt landlocked, beaten down by the monotony of sameness that often plagues an adventurous spirit when he or she is in one place for too long. I moved to Ireland and licked Dublin’s cobblestone streets. I returned to Seattle to loose my marriage and then flew as far away as I could to New Zealand in search of whatever it was that was missing from my life.

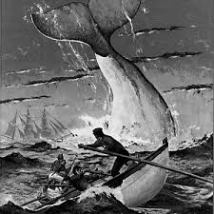

Moby Dick is told from the perspective of Ishmael: a young man on a three-year whaling expedition captained by the mad one-legged Ahab. It’s not long after the Pequod pushes out enroute to the South Pacific that the crew comes to realize that they’re a means to execute Ahab’s obsession to find and kill the elusive white whale whom took his leg some years before. Ahab’s obsession becomes the crew’s ultimate goal as well; and as their ship sails deeper and deeper into the nothingness of the sea, the greater the myth of the white whale grows, until the sperm whale becomes an enigmatic monster of the deep. The leviathan transcends his massive bodily form and becomes a metaphor.

The white whale…

I had a dream as a teenager that I was sitting on a thick limb of a powerful tree looking out onto the Puget Sound when surfaced a giant white whale under the reflection of a full moon. The moonlight emanating from his slippery white skin filled me with a feeling that everything in my life will work out, and that success and happiness will accompany every endeavor I choose to explore. I’ve always remembered this dream as it was the most powerful dream I’ve ever had. I never knew that Moby Dick was a white whale until I begun the novel.

So, the deeper I crawled into the book the more vivid my recollections of this dream became. And beyond, the further into the book I sailed, the clearer the reflections of my time in Ireland, and the most current memories of New Zealand, returned to me. Faces, landscapes, moments of joy, or sorrow, of peace and war leaped from the pages in the strangest of ways.

The description of a sperm whale’s skeleton reflected the roads, alleyways, byways and trails I’ve traveled. The ship’s young lookouts becoming mesmerized by the expanse of the sea and overanalyzing its meaning while standing precariously on top of the Pequod’s main mast at the expense of their falling, awakened me to how I have overanalyzed the many components of my life that I have no control over. Likewise, Captain Ahab’s obsessiveness reminded me of my own slip into codependence that as of late I’ve found a terribly embarrassing feature I’ve acquired through the loneliness of travel. The sea itself, as depicted in the novel, became the vast openness of life. The white whale: the elusive corpus of meaning that I’ve been hunting for since I left home.

Ahab’s monomania subjugates him from everyone else and walled him inside his cabin. He speaks of nothing else, thinks of nothing else, but the white whale. All the interactions available to him, the sea of possibility that he drifts aimlessly on, the plethora of other whales caught by the crew and rendered for their precious oils, is ignored; and so the whole world it seems is passing him by. He is not living, but yet alive. Reading on, Moby Dick, the metaphor, became too huge to ignore. Without realizing it, my own story became enmeshed in Ishmael’s narrative. I was no longer reading a novel as much as I was reading into myself.

The white whale I chase is the unattainable measurement I have applied to what it means to be living life to the fullest; the whale is the impossible standard of intellectual potential I fail to match; the unrealistic parameters I’ve applied on loving and being loved; the unfair expectations I place on others. So what is the white whale really?

Ishmael joined the Pequod in search of adventure. However, his adventure became ensnared in the obsession of another. Conversely I’ve found, in the hunt of what it is to be a man, that I’ve been a man for a while now, but acting under the naive and impossible assumptions of manhood founded by the boy that dreamed of the white whale years before. The white whale is exactly enigmatic, mythical, and a monster because he is a complete waste of time. The whale symbolized everything that opposes living; he is the ghost we chase in the dark; the fractured echoes of the past that cannot be changed. He is the hurt and the pain that we hold onto instead of living. At some point the hunt has to stop. The present must prevail.

It’s funny how a book can hurt then heal you. It still amazes me how deep the form can dig into one’s life. The novel has the power to expose to each and every one of us the inner workings of the human condition. It has the ability to find you.

I suppose I had to come home to break a cycle. I’ve been leaving things for too long now. Chasing ghosts and taking for granted the many gifts I’ve been given by so many amazing people. I think it is time to start going places for a change. My adventures are not nearly over. New Zealand for example was a place I went to in order to run away from somewhere else, and because of that, I began to destroy myself like Ahab let the white whale destroy him. I was lonely even when surrounded by some of the most amazing people I’ve ever met. All for the sake of chasing down an idea of a man that I already was.

For now I know that from now on home is wherever I am. There is no need to worry about anything else. No doors are closed. New Zealand is always there and so is everywhere else. A novel taught me this.

“Thus, I give up the spear!” -Ahab